PAIN.

Be it physical, mental or emotional, pain is the number one reason people seek medication, legal or illegal. On average, 115 Americans die every day from an opioid overdose. The root of the problem is pain.

Physical Pain

In his early 20s, Alex Miles began experiencing back pain. Over time, it became so bad it drove the otherwise healthy young man to seek medical attention.

“MRI’s and X-rays showed nothing. My hips are normal; no arthritis in my lower back,” Miles was told.

He started on acetaminophen, then acetaminophen with codeine. His pain continued to increase, as did his tolerance for the meds. Each time he was handed a stronger prescription, it came with the doctor’s admonishment: “This is not a long-term cure.” Alternative treatments like acupuncture and physical therapy were tried to no avail.

Three-and-a-half years later, still with no diagnosis, as his pain and corresponding dependence on opioids grew, the prescriptions weren’t enough. Seeking relief, Miles began to “supplement” his prescribed pain meds with marijuana. And then one day, he failed a random drug test his doctor administered. The prescriptions stopped abruptly.

Addicted and abandoned, Miles felt he had no alternative but to turn to the street, where prescription opioids cost about $1 per milligram.

“So, it cost me about $150 a day to get the pain pills I needed just to function. I wasn’t getting high. I wasn’t having fun,” he said.

The cost unsustainable, Miles ultimately turned to heroin, providing adequate pain relief for an affordable $50 per day but with the unspoken price of a monstrous addiction. Perhaps the saddest part of Miles’ story? It’s run of the mill. It is happening every day.

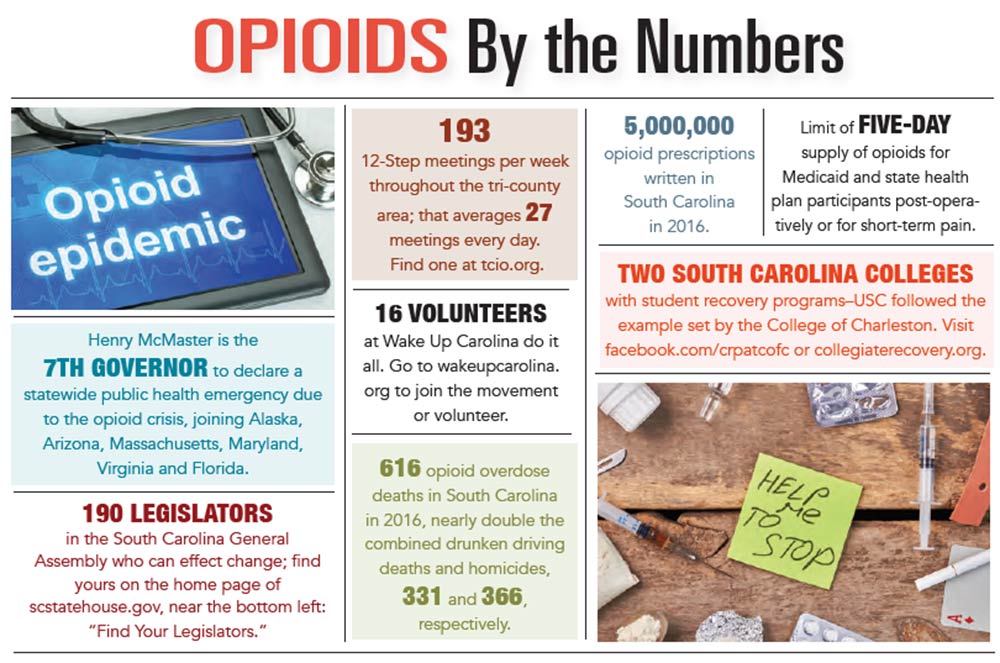

“It is a full-blown law enforcement and public health crisis of historic proportion,” Jason Sandoval, Drug Enforcement Administration resident agent in charge for Charleston, stated emphatically. “In 2016 alone, we lost 64,000 lives.”

These deaths were directly related to drug overdoses, 63 percent of them from opioid and heroin abuse.

“Crisis? Definitely not an overreaction,” Sandoval concluded.

It gets worse. The numbers in South Carolina are staggering, as Sandoval detailed statistics showing deaths in Charleston County in 2017 “were 150-percent higher than the national average.” A total of 105 people died from an opioid drug overdose in the tri-county area in 2016, 65 of them in Charleston County.

Mental and Emotional Pain

Growing up, Andrea Jackson never felt she measured up to her peers. In her mind, she was never “good enough.” So at 19, when presented with a small bowl full of pills at a party, she eagerly popped one, just as most of the other kids were doing.

“We stole them from our parents,” she recalled unabashedly, as 40 percent of teens across America admit to doing. “Once I ate it, it was as if someone had flipped a light switch. Suddenly, I was everything I’d always hoped to be and more.”

Ten years later, the petite 29-year-old brunette was suicidal.

“I had a good job; I thought I was holding it together for the outside world to see. But on the inside, I was a hot mess,” she said.

Because of the cost, she’d “graduated” to heroin, which “numbed my emotional pain. I was mentally obsessed and physically addicted. I hated myself and what I had become – an addict, snorting $100 worth of heroin a day. But anything was better than the way I felt sober.”

The medical effort to ease pain has been around since 3400 B.C., when ancient Sumerians cultivated the opium poppy. Fast-forward to the mid-1800s, when thousands of Civil War veterans were diagnosed with “the Army Disease,” an addiction to morphine.

“Morphine and opiates were seen as miracles of medicine, and their steady supply made them the first line of defense for every condition, which easily translated into widespread addiction,” offered the Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History.

History has yet again repeated itself. “OxyContin” could easily replace “morphine and opiates” in the preceding sentence and present a convincing explanation for the onset of our current crisis. When OxyContin hit the market in 1996, it was touted and sold to the medical community as a miracle drug, a “safe” opioid alternative. It was safe because it is time-released and consequently not as likely to produce the euphoric highs and depressing lows of its predecessors – no highs, no cravings.

Coincident with the introduction of this amazing new drug, the medical community was shifting its collective thinking on chronic non-cancer pain. Pain became “the fifth vital sign,” and the ubiquitous emergency room query: “On a scale of one to 10, what is your pain level?” became the second question asked of every patient, preceded only by “do you have insurance?”

Whereas opioids had previously been prescribed primarily for cancer patients, “Oxy” and its siblings Vicodin and Percocet were pushed by the manufacturers and embraced by primary care physicians as the solution for moderate pain for everything from lower back pain to tooth extraction.

A perfect storm developed as insurance companies began to reimburse for pain meds but not alternative forms of pain management. Furthermore, the FDA-approved warning label on OxyContin, cautioning “Do Not Crush,” inadvertently attracted addicts, like a neon sign, basically providing instructions for abuse.

So What’s To Be Done?

“Most health care in the United States is regulated on the state level,” wrote Gary Franklin, MD, in the March 2015 issue of the American Journal of Public Health. “Both cause and cure come from state action.”

Taking action is exactly what South Carolina is doing. In December 2017, Gov. Henry McMaster declared a statewide public health emergency and appointed an Opioid Emergency Response Team.

State funding supports the cutting edge Pain Rehabilitation Program at the Medical University of South Carolina, the first and only program in the Palmetto State for “rehabilitating patients with chronic pain that originally needed opioids,” stated Dr. Kelly Barth, medical director. MUSC’s program is designed to derail the addiction train that Miles rode, “tapering and eliminating” the use of opioids for chronic pain, attacking dependence across medical disciplines, including behavior therapy, physical and occupational therapy and nutrition.

“Seven million people are stuck on opioids that are no longer working but don’t qualify for addiction treatment,” stated Dr. Barth, as was exactly the case with Miles. “We have ways to address these symptoms and give patients the support they need to come off opioids and get back to living a full life. We cannot merely reduce the supply of opioids; we need to reduce the demand.”

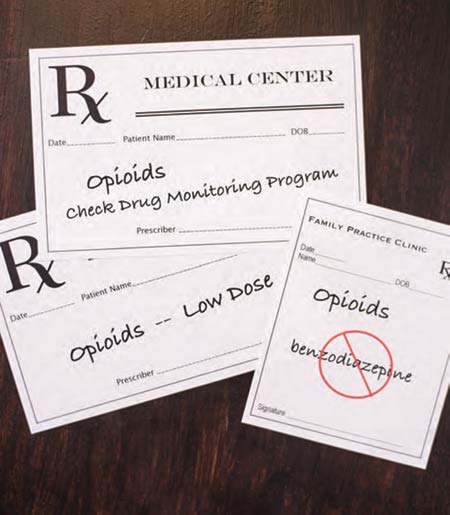

South Carolina also has developed a statewide prescription monitoring program, SCRIPTS, administered by the Department of Health and Environmental Control. SCRIPTS requires a prescriber to check a patient’s history prior to prescribing Class ll through lV controlled substances, which include opioids. If the patient has been prescribed opioids in the past, it identifies the prior prescriber and the dispensing pharmacy.

Legislation is in committee to establish continuing education requirements for prescribers. When she broke her ankle, Mary McGregor told her highly recommended orthopedic surgeon, “I am in recovery. Please do not prescribe any narcotics for me.” She elaborated, “Pills were never my problem, but I have the mind of an addict. I become mentally obsessed. My sobriety is my most prized possession, and I’m not taking anything which might put that in jeopardy.”

Upon discharge, unbeknownst to her, the doctor slipped her husband a prescription for 60 OxyContin, “just in case she needs them over the weekend.” McGregor doesn’t believe her surgeon had bad intentions. “He was just not educated. He didn’t understand. Sixty pills is easily a new addiction. If he was concerned I would call him over the weekend, he should have prescribed a two-day supply.”

Other bills are being considered – some extremely simple and just basic common sense: Develop and mandate the use of counterfeit-proof prescription pads, for example.

In addition relying on the state to legislate changes, a powerful grass-roots movement, born of a local tragedy, is beginning to bring the problem to light.

“Mom, we can’t let another family go through this,” cried Nanci Steadman Shipman’s daughter, as her stunned, heartbroken family surrounded the deathbed of her brother, a young man you’d never dream would succumb to the disease of addiction.

Wake Up Carolina, the resulting nonprofit, seeks to smash the stigma of addiction.

“No one is immune to this disease,” stated Shipman, whose son Creighton ultimately became addicted as a result of being treated for a sports injury, a story remarkably resembling Miles’ – actually, not remarkable.

A local group of oral surgeons has teamed up with health insurance giant Aetna in a pilot program designed to reduce opioid prescriptions with the use of a new, non-narcotic drug called Exparel.Opioid addiction “is becoming a major concern for parents,” stated Dr. Aaron Sarathy of Charleston Oral and Facial Surgery, whose practice was selected for the pilot study. Among 10-year-old to 19-year-old patients, dentists are the main prescribers of opioids. As an oral surgeon, Dr. Sarathy routinely faces the decision to prescribe opioids for patients having a wisdom tooth removed. With Aetna now covering the cost of Exparel, Dr. Sarathy is beginning to see more patients opting for it as an alternative to an opioid prescription.

A local group of oral surgeons has teamed up with health insurance giant Aetna in a pilot program designed to reduce opioid prescriptions with the use of a new, non-narcotic drug called Exparel.Opioid addiction “is becoming a major concern for parents,” stated Dr. Aaron Sarathy of Charleston Oral and Facial Surgery, whose practice was selected for the pilot study. Among 10-year-old to 19-year-old patients, dentists are the main prescribers of opioids. As an oral surgeon, Dr. Sarathy routinely faces the decision to prescribe opioids for patients having a wisdom tooth removed. With Aetna now covering the cost of Exparel, Dr. Sarathy is beginning to see more patients opting for it as an alternative to an opioid prescription.

“Ibuprofen is the workhorse of pain management,” stated Dr. Sarathy, one of four surgeons at COAFS. “The primary need for opioids occurs 12 to 24 hours post-surgery, just to take the edge off.”

Administering a dose of Exparel during the procedure may reduce and possibly eliminate the need for opioids. A long-lasting analgesic, Exparel may well be an answer to the opioid crisis, providing non-narcotic relief for short-term post-op pain.

Julie Lawrence, PharmD, BCPS, a volunteer for Wake Up Carolina, agreed: “We’re coming full-circle. We’re reverting to old-school, regularly scheduling doses of ibuprofen and acetaminophen. We’re finally starting to revamp pain protocols and dial back on opioids while still keeping people comfortable.”

It’s Happening Every Day

Rehabs often rely on drug-replacement therapies, such as methadone and Suboxone. However, these substances are opioids themselves and therefore can be habit-forming.

Many experts in the field of addiction agree that any reputable rehab is going to include a 12-step program.

Detoxing is one way to completely come off of opioids.

“Many chronic pain patients express a desire to come off their meds,” explained Dr. Barth, “but fear feeling symptoms of pain and withdraw.”

Justifiably so. Detox “is indescribable,” bemoaned Miles, who after several rehabs ultimately chose to endure “four days of pure hell. It’s like the worst flu you can imagine, combined with unbelievable anxiety.”

And yet, despite his horrific experience, Miles takes naltrexone, an opioid blocker, as a precaution, to head off any potential cravings. Jackson, who detoxed eight years ago, has remained clean and sober through the regular practice of a 12-step program.

Creating a “reverse” stigma with young people may be one long-term solution. Drunk driving has been successfully stigmatized; it’s a given with most younger drivers – they just don’t do it. A similar contempt for “recreational” opioid use may be instilled with legislated student education, currently in committee, and organizations such as Wake Up Carolina. Peer pressure can be a powerful tool, as can the crushing loss of a “rock star” like Creighton Shipman. It’s unrealistic to think teenagers will ever stop experimenting, but opioid use needs to be removed from the equation and become taboo.

Sandoval, the DEA agent, conservatively estimated another quarter-million Americans will be lost “before we are in front of the crisis.”

“How many more people have to die before we start doing something?” he asked passionately. “No one wakes up and says ‘Today I’m going to destroy my life and devastate my family.’ No one chooses a lifestyle of mental anguish.”