An old Colonial-era saying claimed, “South Carolina is in the spring a paradise, in the summer a hell and in the autumn a hospital.” In subsequent centuries, the South Carolina Lowcountry has retained its springtime sumptuousness, while the hellishness of its summers has been exorcised somewhat by the advent of mosquito control, air conditioning and sweet tea.

Charleston’s once-autumnal function as a “hospital,” however, has grown into a year-round role that the city’s leaders proudly embrace. Though the road to the Holy City’s current status as a regional health care hub has not been without its bumps and potholes, Charleston has come from being what medical historian Peter McCandless called “the deadliest disease region on the North American mainland” to a nationally recognized center of healing.

PARADISE TAINTED

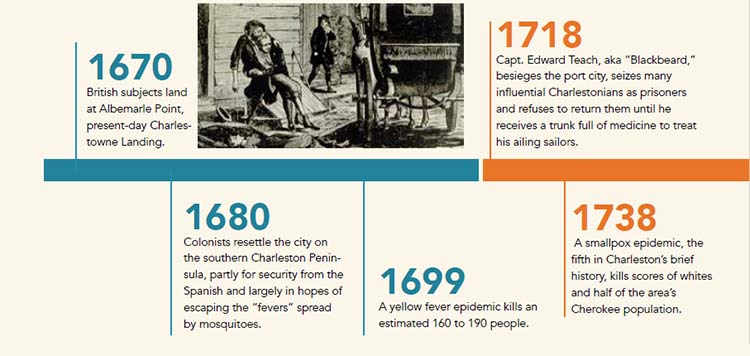

The indigenous peoples who summered for centuries on the South Carolina coast did so with few worries other than sunstroke, sand fleas and alligators. With European contact, however, the arrival of exotic diseases – smallpox in particular – decimated the local native population within a generation.

The British subjects who landed at Albemarle Point in 1670 resettled Charles Town on the southern end of the Charleston Peninsula within 10 years, in part due to the prevailing breezes that thinned out the mosquito population. Mosquitoes had always been plentiful on the Carolina coast but yellow fever had not. The enslaved West Africans imported to the region for their rice-growing expertise brought the fever with them.

Though many of the Africans were immune to the disease because they had been exposed to it previously, white Carolinians were not. The annual epidemic brought plantation owners flooding into their peninsular town homes or off to summer houses during the hot weather months while their enslaved field workers continued clearing the swamps and expanding the rice fields that, of course, created more breeding grounds for mosquitoes.

Two of Charleston’s best-known Colonial-era physicians are best remembered for their extracurricular research. Scotland- born John Lining arrived in 1730, noticed the connection between the weather and the city’s notorious health issues and soon began his famous, pioneering weather observations. He hoped, among other things, to discover “the influences of our different seasons upon the human body; by which I might arrive at some more certain knowledge of the causes of our epidemic diseases.”

Lining also replicated Benjamin Franklin’s electricity experiments, which helped lead to the adoption by many Charlestonians of lifesaving – and building-saving – lightning rods. He also studied human metabolism, using himself as the chief subject, and even launched experiments to determine the long-term effects of deforestation on rainfall and temperatures.

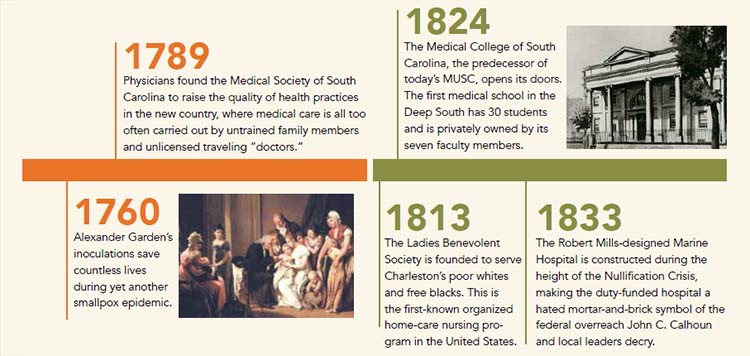

His fellow Scotsman, Alexander Garden, for whom the gardenia flower is named, arrived in the 1750s and quickly became a member of a thriving local medical practice. However, he spent much of his off time collecting, studying and shipping flora and fauna samples to fellow natural scientists back in Europe. Nonetheless, the young physician proved invaluable during Charleston’s 1760 smallpox epidemic, performing controversial inoculations on some 2,000 residents and saving untold lives. His career and hobbies came close to uniting when he published an essay on the medicinal uses of the pinkroot, but Garden was forced to leave the country after siding with the British during the Revolutionary War.

Charleston has come from being what medical historian Peter McCandless called “the deadliest disease region on the North American mainland” to a nationally recognized center of healing.

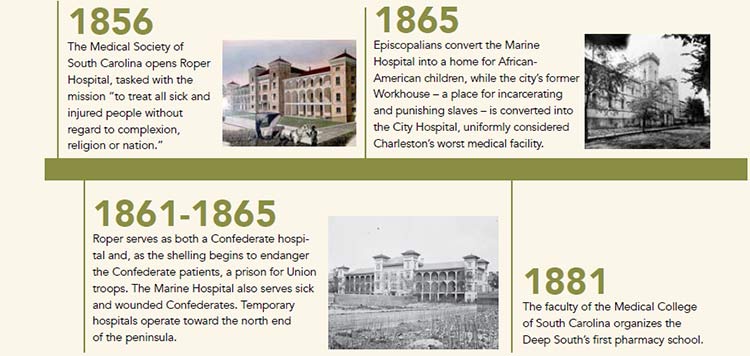

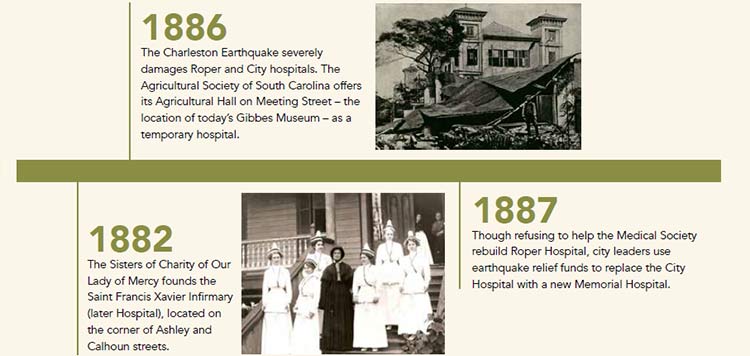

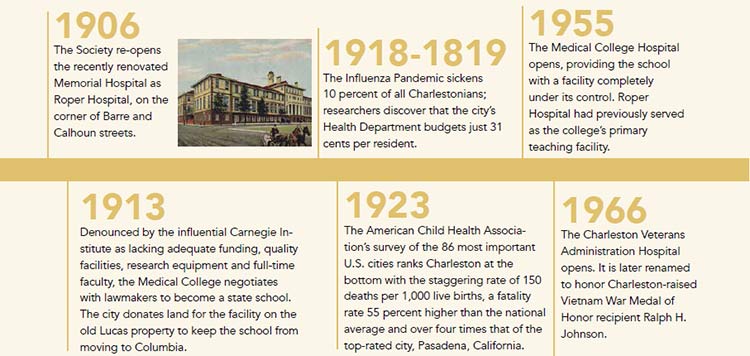

The caring work and groundbreaking research of Charleston’s physicians continued in the years to come. A group of doctors founded the Medical Society of South Carolina in 1789 with the expressed purpose of “improv[ing] the Science of Medicine, promoting liberality in the Profession, and harmony amongst the practitioners in th[e] city.” Before a hundred years had passed, Charleston boasted four major hospitals, one medical college, two nursing schools and nearly 70 physicians and surgeons.

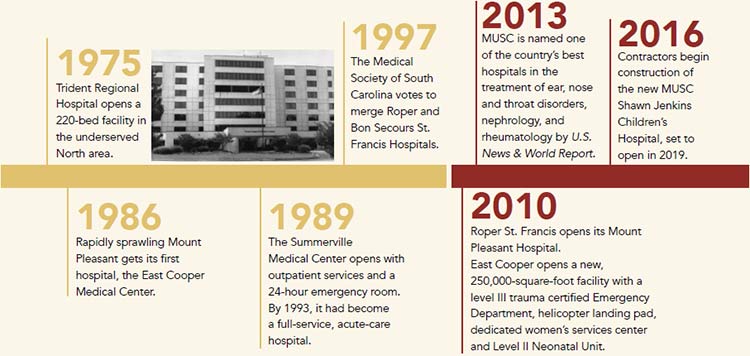

The new Medical College Hospital arrived in 1955, and the VA Hospital opened 11 years after that. In 1970s and 1980s, hospitals were erected off the peninsula to serve residents of the greater metropolitan area, and the subsequent decades have seen even more new facilities open to Charleston’s east, west and north.

Today, the Veterans Administration, MUSC and Roper St. Francis are working together with the city of Charleston on the city’s Medical District Initiative to increase green space, walking areas, parking, signs and easier access to downtown’s major health care centers. In addition to the clinical care provided at all three hospitals, the medical district itself is meant to foster a healing environment for patients.

WHAT’S MISSING?

What gaps remain in the Lowcountry’s health net? A survey of local hospital leaders brought some thoughtful answers. Dr. Patrick Cawley, CEO at MUSC, saw no gaps in the region’s services, per se, yet even with Charleston’s wealth of trained personnel and cutting-edge facilities, each of the leaders acknowleged that room for improvement exists when it comes to accessibility. Both Summerville Medical Center CEO Lisa Valentine and Trident Medical Center CEO Todd Gallati agreed, for instance, that a significant gap exists between the need for behavioral health services and the availability of those services – though they’re both quick to point out that this is a statewide and even a nationwide problem.

What gaps remain in the Lowcountry’s health net? A survey of local hospital leaders brought some thoughtful answers. Dr. Patrick Cawley, CEO at MUSC, saw no gaps in the region’s services, per se, yet even with Charleston’s wealth of trained personnel and cutting-edge facilities, each of the leaders acknowleged that room for improvement exists when it comes to accessibility. Both Summerville Medical Center CEO Lisa Valentine and Trident Medical Center CEO Todd Gallati agreed, for instance, that a significant gap exists between the need for behavioral health services and the availability of those services – though they’re both quick to point out that this is a statewide and even a nationwide problem.

For the VA’s Scott Isaacks, the lack of accessibility is a concrete issue – literally. His hospital needs more parking: “We’ve taken a number of steps to improve the parking situation, including building a new parking deck – which is set to open later this year – leasing off-site parking spaces and offering valet service for patients. We are committed to making parking easier for veterans and work continually to find manageable solutions to address our parking needs.”

ACCESSIBILITY AND DEMOGRAPHICS

The VA’s parking issues are just one of many symptoms of the elephant in the waiting room. The force behind Charleston’s biggest medical challenge in the coming decades is the torrent of people moving into the area and the logistics of providing quality care for all these new arrivals. For example, Valentine suggested that the need already exists for advanced pediatric critical care services and Level III Neonatal ICU in the Summerville area. “Our growing communities need these inpatient hospital based services closer to home,” she said.

Roper St. Francis’ David Dunlap agreed: “An estimated 75,000 people are expected to move into Berkeley County in the next 20 years, and yet they still don’t have a full-service hospital to serve their community.” He pointed to the planned 60,000-square-foot, full-service Roper St. Francis Berkeley Hospital, currently in its planning stages, with groundbreaking expected in early 2017.

Isaacks reported that the VA already feels the crush: “We see anywhere from 700 to 900 new patients a month – a tremendous growth rate for a facility our size. Serving such a large population poses unique challenges given our space constraints, especially at our main site in downtown Charleston.”

While the Charleston hospital has expanded its GI laboratory rooms and is enlarging its ICU and Emergency Department, like the other hospitals in the region, the VA is making efforts to reach out to its patients where they live. “We’re opening a new outpatient clinic in Savannah,” Isaacks noted, “and have plans to open a larger consolidated clinic in Myrtle Beach. We also offer select specialty services at our community-based outpatient clinics to decrease the number of patients needing to visit the main site for care.”

FINDING NEW WAYS

As one might expect, the leaders of Charleston’s hospitals see the future of Lowcountry health care to be shaped by efforts to maximize accessibility despite the area’s swelling and sprawling population. To this end, nearly everyone discussed telehealth. MUSC’s Cawley touted the sheer convenience “for patients and families to be able to see the doctor in the comfort of their own home via a telephone, a smartphone or a home computer.”

Valentine agreed that telehealth is the way of the future: “[It enables] patients to have 24/7 access to extraordinary specialists. I expect in the coming years, you’ll see this type of technology increasingly expand to physician consultations via computer/ phone, making the experience more accessible for many.”

“The next biggest thing you’re going to see is a much more aggressive push into keeping people healthier: We know that if we can get ahead of some of these things, we can keep people healthier for longer periods of times, which leads to greater quality of life overall. We also know that this is less expensive over time.”

“Telehealth truly opens the door to wellness,” Isaacks stated, “and drastically increases access for rural patients who would normally have to travel long distances to receive care – and for those struggling with the stigma of presenting in person for their appointments, such as patients seeking mental health care.”

By maximizing access to preventive care, the CEOs hope to avert thousands of hospital visits a year. Roper’s Dunlap explained: “We know a small number of sick patients consume the majority of our resources. Population health management, or being more proactive in helping those patients with chronic conditions manage their care to keep them out of the hospital, is an issue we are working on. It will become even more important in the next decade.”

MUSC’s Cawley agreed: “The next biggest thing you’re going to see is a much more aggressive push into keeping people healthier: We know that if we can get ahead of some of these things, we can keep people healthier for longer periods of times, which leads to greater quality of life overall. We also know that this is less expensive over time.”

Gallati suspects that the next decade will probably introduce breakthrough treatments for cancer and cardiovascular care. While Cawley made no specific predictions, he spoke with an optimism and confidence common to all the city’s health leaders and reminiscent of John Lining and Alexander Garden: “There are numerous things I see every day at MUSC that are going to help patients in the future. Some of those are what we call basic science, things that we’re learning about diseases and how they affect the human body that may not have a solution tomorrow but certainly will put us on the path to curing something or offering a better therapy in 10 years. Sometimes those, to me, as a physician, are the most exciting, because it may lead to a completely different way of doing things.”

By Michael Sigalas