Factors outside of their control prevent many South Carolinians from achieving good health. This issue has been hitting the headlines recently as people realize that not everyone is on a level playing field when it comes to getting and staying healthy. Healthy People 2030, a federal initiative seeking ways to improve health, describes these differences as health disparities, which are closely linked to social, economic or environmental disadvantage.

According to the Alliance for a Healthier South Carolina, people most affected by these differences are “minorities, children living in poverty, people with different gender identity and sexual orientation, people facing major mental or physical disabilities and families living in underserved regions, primarily those living in rural communities.”

Dr. Marvella Ford, associate director of population sciences and cancer disparities at the Medical University of South Carolina’s Hollings Cancer Center, sees the serious impact of these health disparities every day.

“The COVID-19 pandemic brought more attention to the inequalities in how people receive care, given the disparities in COVID-19 death rates by race and ethnicity,” she explained.

Dr. Ford has been studying the problem and identifying innovative solutions with colleagues throughout her career. She recognizes that disparities affect an entire community.

“We all benefit when a community is healthy, leading to greater productivity and economic prosperity,” she said.

HPV Vaccination Van Program

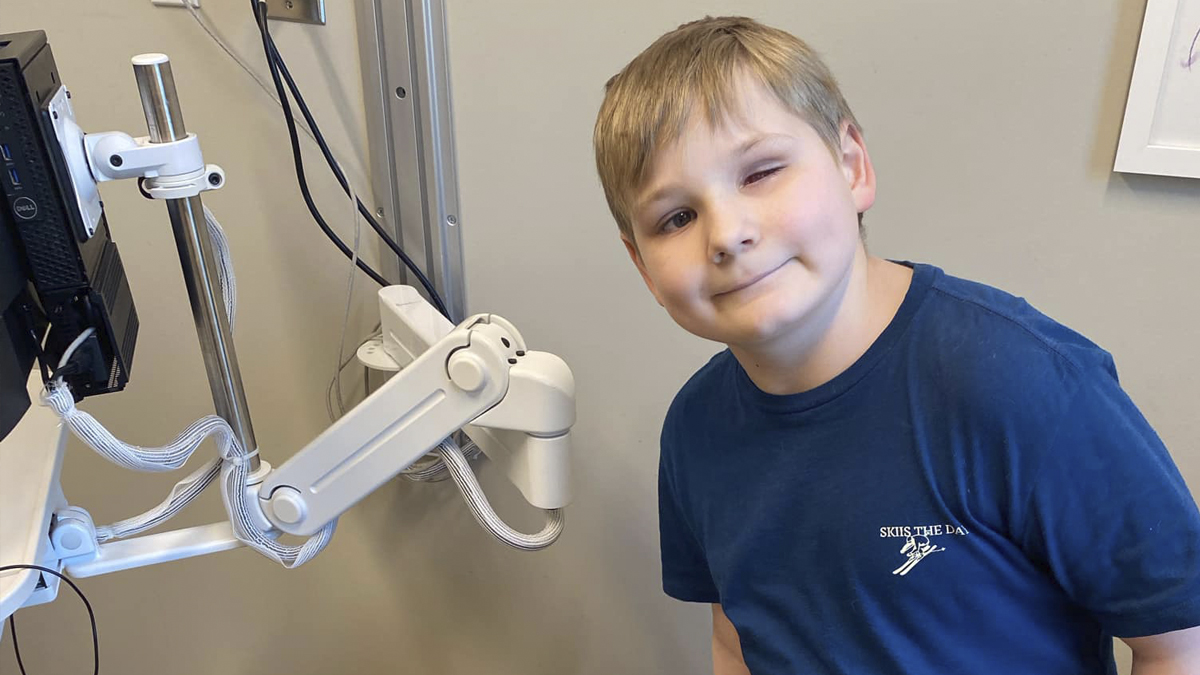

Dr. Ford is an integral part of one initiative closing the gap in care – the HPV Vaccination Van program. Developed in 2021 by MUSC’s Hollings Cancer Center and Department of Pediatrics, the program was a reaction to the discovery of significantly lower rates of human papillomavirus vaccination in rural and medically underserved areas of South Carolina. HPV infections are linked to at least six different types of cancer. Health professionals travel to schools, health fairs and community events in a brand-new mobile health unit to provide education and administer vaccines, reaching people in the highest-need areas of the state who might otherwise not know about the benefits of or how to obtain a vaccination.

Lung Cancer Screening

Dr. Ford also played a role in a study looking at lung cancer screening guidelines. Existing standards do not consider racial, ethnic, socioeconomic and sex-based differences in smoking behaviors or lung cancer risks that affect who is more likely to suffer with or die from the disease. The study identified strategies such as assigning patient navigators who help patients understand their treatment options and providing training for providers on communication techniques to build patient trust.

Infant Mortality

Dr. Edward Simmer, the director of the South Carolina Department of Health and Environmental Control, sees disparities affecting almost all areas of health care but believes that infant mortality and chronic illness should be two priorities in the Palmetto State.

According to the DHEC website, in South Carolina, Black women are significantly more likely to suffer adverse outcomes during pregnancy and childbirth, and their children are more likely to die in the first year of life, at a rate nearly 2.5 times that of white infants. According to Dr. Simmer, “Many of those deaths are preventable through education and greater access to care. So many lives would be saved if we do the right thing.”

The state collects data on health disparities, where they exist and how they affect a community’s health. Dr. Simmer challenges his staff daily: “Now how do we turn data into things we can change?” DHEC has employed successful strategies including educational programs like ABCs of Safe Sleep for Infants and a robust newborn screening program that evaluates newborns for 54 disorders. But much more needs to be done to close the gaps in health outcomes.

Dr. Simmer said access to prenatal care is a major driver of health disparities in rural communities.

“Patients need care at a location they can get to, when and where they need it. A lot of patients do not have good transportation to reach a provider, and 14 counties in the state do not have a gynecologist,” he said.

Telehealth is one strategy that providers and facilities are expanding, but broadband access is still an issue in some areas. Another option the state is exploring is the use of mobile OB/GYN services because, Dr. Simmer said, “We need to bring care into communities where it doesn’t exist today.”

Chronic Diseases

Data shows that racial and ethnic minorities across South Carolina experience higher rates of illness and death from chronic conditions such as diabetes, obesity, asthma and heart disease, when compared to their white counterparts.

Dr. Simmer believes that the lack of access to both education and treatment contribute to these gaps. According to the CDC, communities can help prevent health disparities when community- and faith-based organizations, employers, health care systems and others work together. Dr. Simmer concurs: “We work with many local, trusted organizations because they know the community best, and people will listen when health education is led by someone they can trust.”

Dr. Ford believes that part of the solution to addressing disparities is to mentor young adults from racially and ethnically diverse backgrounds as they train to become the next generation of health care practitioners and public health professionals. With a greater understanding of health disparities and ways to address these gaps, residents will have the chance to help achieve the vision of the Alliance for a Healthier South Carolina: to give all South Carolinians the opportunity to achieve their optimal level of health and well-being.

By Lisa Wack