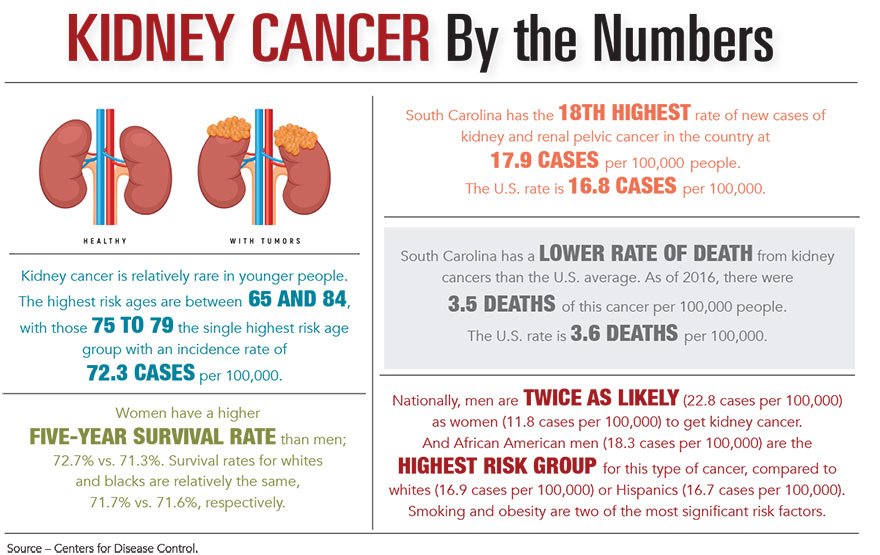

Overshadowed by cancers of the lung, breast and pancreas, kidney cancer often flies under the radar. Nonetheless, nationally it is seventh on the top 10 cancers ranked by new cases, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Although nephrologists are the kidney specialists, when cancer is suspected, a patient is most likely to see a urologist or an oncologist.

Dr. Stefanie Seixas-Mikelus is both. She launched East Cooper Urology, part of The East Cooper Medical Group in Mount Pleasant, last July, and she is currently the sole urologist on staff.

There are different types of kidney cancers, but they break down into two most common varieties:

- Cancers within the “meat” or parenchyma of the kidney itself, called renal cell carcinomas that account for about 85% of cases;

- Tumors in the “pipes” or the “collecting system” of the kidneys, like the renal pelvis or the ureter, called transitional cell carcinomas that make up about 10% of the cases.

Over the past 20 years, the rates of kidney cancer have been rising, but, at the same time, deaths have been holding relatively steady or falling slightly, according to data from the National Cancer Institute at the National Institutes of Health.

South Carolina mirrors this trend with kidney cancer ranking seventh in cases but 13th in mortality.

That trend, however, is not an inconsistency to Dr. Seixas-Mikelus – It’s really cause and effect.

Kidney cancers historically presented late and at a higher stage, with up to a third identified at stage four. But the increased prevalence of diagnostic imaging has resulted in much earlier detection and better outcomes.

“We often nickname renal cell carcinomas ‘incidentalomas’,” she said, “because they are uncovered during an imaging scan for another condition. In the not-too-distant past, these cancers wouldn’t be identified until patients experienced the most severe symptoms: blood in the urine, back pain or weight loss. They were much more advanced and often had already metastasized. Now with all the imaging modalities available for use for other reasons, it tends to be an incidental finding. We’re fortunate that we find the majority of kidney cancers now at a much earlier stage. Prognosis is always better if you catch them at an early stage.”

It’s not surprising the state has higher rates of kidney cancer when you look at the key risk factors. At the top of the list, Dr. Seixas-Mikelus noted, is smoking.

“Lifetime exposure and volume play an important role. The longer the duration and the amount correlates with a higher risk of types of kidney cancers. But we also know that if you stop smoking that it actually decreases your risk, particularly with transitional cell carcinomas, not only of the kidney but also the bladder, and the risk of progression and recurrence goes down.”

She cautioned that an ex-smoker’s probability never falls back to the level of a nonsmoker, but “quitting smoking is always a good idea, and it’s never too late to decrease your risk.”

Obesity is also a well-established risk factor as well as a known health concern for South Carolinians. According to the CDC, 34.3% of the state’s residents are obese.

There can also be hereditary risk factors, she noted, specifically from a number of conditions like von Hippel-Lindau disease, hereditary leiomyoma-renal cell carcinoma, Birt-Hogg-Dube syndrome or a specific genetic defect that results in a strong family history of renal cancer.

Treatments can vary depending on a number of factors, including age, overall health condition and the type of cancer, size of tumor and location. Surgery to remove the lesion may be preferable for healthy younger patients, Dr. Seixas-Mikelus explained, but older patients with comorbidities may not be good surgical candidates. Ablation may be an option for renal cell patients if the tumor is small enough, she said.

Because small renal cell tumors grow slowly, she sometimes recommends “active surveillance” – a wait-and-see approach with periodic imaging – as the best course of action.

Two standard treatments for many kinds of cancer – chemotherapy and radiation – are not as readily used in treating kidney cancer, according to the American Cancer Society.

Kidney cancer cells do not respond particularly well to chemotherapy, which makes this normally-standard component of fighting cancer a rarity in kidney cancers. According to the American Cancer Society, there are a few chemo drugs that have been shown to help with a small number of patients, but they are usually only given after immunotherapy or other targeted drugs have been tried.

Radiation, the organization said, is only “sometimes” used and most often as a palliative treatment rather than a curative one.

Women urologists are a rarity, Dr. Seixas-Mikelus noted, adding that a decade ago “there were maybe 500 board-certified – today maybe 1,000.” She’s also one of a smaller number of women urologists who treat both men and women patients.

“After finishing my fellowship, there were perhaps a dozen in the country trained in robotic surgery, let alone urologic oncology,” she said.

In her previous position, Dr. Seixas-Mikelus was the medical director of robotic surgery at Hackensack Meridian Jersey Shore University Medical Center in New Jersey.

So it’s not surprising that when surgery is the best option, Dr. Seixas-Mikelus prefers robotic procedures to open surgery.

“There’s much less blood loss, smaller incisions, less need for post-op narcotics, quicker recovery and less scarring,” she noted.

All are important elements for overall better outcomes. While she is an expert in robotic surgery, Dr. Seixas-Mikelus’ training took place through the evolution from “open to laparoscopy to robotics.”

She considers herself “blessed” to have trained during the transition through all these surgical options, noting that new medical students may have little exposure to open surgery.

“There’s a time and place for open surgery, especially if you get bleeding and you have to switch to open. The robot,” she said, “is just another tool in the toolbox.”

By Laura Haight