One spring day in 2000, Greenville County resident Harold Moore was doing his usual job: inspecting facilities, machinery, and safety equipment for potential hazards at the Hitachi Manufacturing Center in Mauldin. When he went to calibrate an instrument for a piece of equipment, Moore couldn’t judge the accuracy of the readings because “the numbers suddenly weren’t clear.”

“Turns out I was nearsighted, and had to get prescription glasses,” said Moore, originally from West Virginia. “Not sure why the condition showed up when it did, as I was almost 40. But it’s gotten worse over time.”

Moore’s condition is somewhat unusual because nearsightedness, also known as myopia, usually occurs within a person’s first 15 years.

But from now until 2050, health professionals across the globe are warning that unless people everywhere, especially in advanced societies such as Europe and North America, make permanent changes in their eye care, a massive increase in nearsightedness is not only expected, but likely to become another pandemic for many more millions worldwide.

“More than half of the world population will be myopic by 2050,” stated Ali Nouraeinejad, clinical ophthalmic adviser with Vision Plus in Buckinghamshire, England, in a 2021 research article for the National Institutes of Health in Bethesda, Maryland.

Nouraeinejad also noted in the same article that such an increase would also tend to make the condition show up at earlier ages.

“The earlier the onset, the more myopic the individual will become later in life,” added Nouraeinejad, who has also served in the Department of Ophthalmology at Tehran University of Medical Sciences in Tehran, Iran. “In this context, the prevalence of myopia has been shown to be more than two-fold over the past 50 years in white British children aged between 10 and 16 years old in the United Kingdom.”

In the United States, ophthalmologists and optometrists are already noting the rise of nearsightedness.

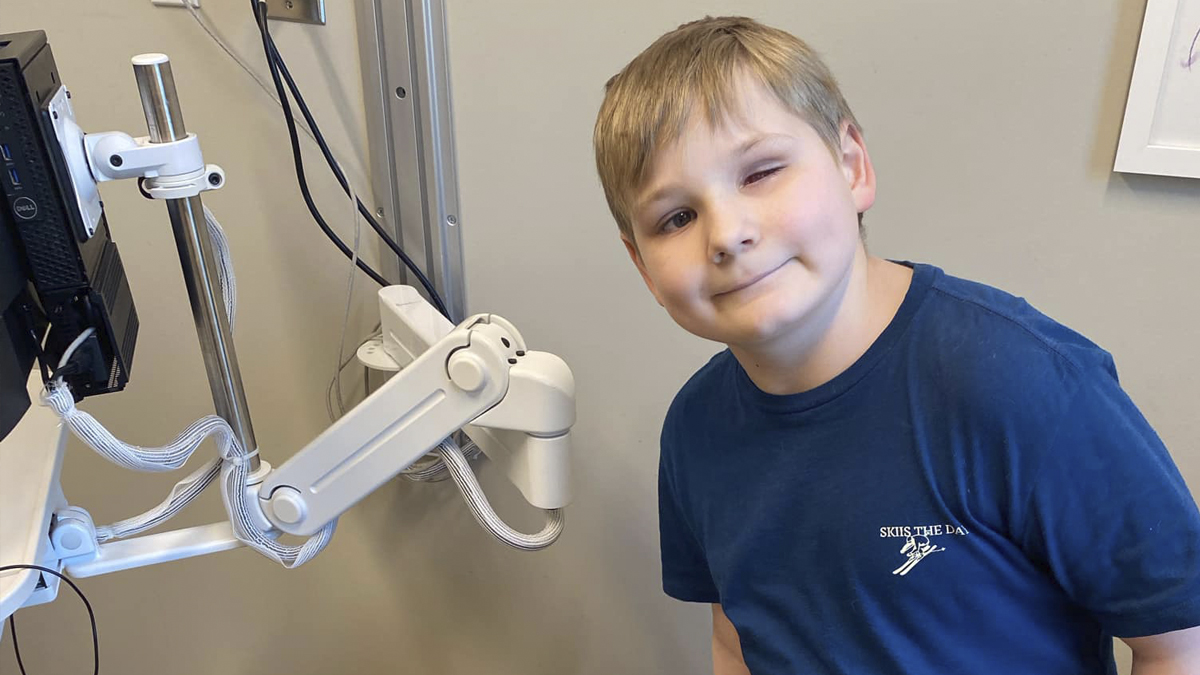

“About 25% of my patients need treatment for nearsightedness,” said Dr. Elizabeth Holland, board certified ophthalmologist and eye surgeon with Holland Eye Center in Greenville, South Carolina. “We commonly see it in kids between the ages of 10-15, with another spike during college from ages 19-22.”

Dr. Justine O’Dell, doctor of optometry with Dr. McGregor & Associates in Greenville, added that nearsightedness accounts for about 50% of their patient cases.

“And since 80% of learning is through the visual system, it is very important for school-age children to have an eye exam,” she said. “This is especially true now due to an increased use of digital devices at younger ages, although certainly there is a genetic component as well.”

And, now, an age component too.

Based on a 2019 report by the World Health Organization, population aging will significantly impact the number of people with eye conditions.

For example, WHO projects that by 2030, the number of people worldwide aged 60 years and over to reach 1.4 billion — an increase of 45.5% from 2017.

WHO further projects the number of people worldwide 80 years and over to reach 202 million — a 47.4% increase from 2017.

And the U.S. Census Bureau is projecting older adults to outnumber children by the year 2034 for the first time in U.S. history.

So, what can you do right now to help keep nearsightedness away?

Holland and O’Dell and their colleagues with the American Academy of Ophthalmology and American Optometric Association offer these options to slow the progression of myopia:

• Wear contact lenses properly.

• Schedule regular eye exams and check for both near- and farsightedness.

• Take medications as prescribed by your ophthalmologist.

• Have surgery when necessary.

• For every 20 minutes of screen time — be it computer, TV, cell phone, or other electronic viewing device — take a 20-second break to view something 20 feet away.

• Spend more time outdoors.

“All of these things help to slow down progression of myopia,” Holland said.

While there is not yet enough hard medical evidence to conclusively connect screen time to nearsightedness, researchers with the National Institutes of Health have reported spending more time outdoors reduces the risk.

“There is solid evidence that exposure to brighter light can reduce risk of myopia,” said Dr. Russel Lazarus in a 2021 article for The Optometrists Network, an online eye resource currently serving more than 1 million people each year. “Peripheral defocus can regulate eye growth. But whether spending time outdoors substantially changes peripheral defocus patterns and how this could affect myopia risk is unclear.”

In addition, both Holland and O’Dell recommend dilating drops, contact lens wear, and a type of myopia control known as orthokeratology — the temporary reshaping of the cornea with specially made rigid contact lenses.

“This is a relatively new type of myopia control, developed in the last 20 years to decrease the rate of progression of nearsightedness,” O’Dell said. “But we encourage more time outside to decrease the risk.”

Which, despite his condition, is probably one reason Moore kept it away until almost age 40.

“I spent most of my time outdoors when I was a kid,” he said. “And except for a stint in the West Virginia coal mines when I was 22-25, I don’t know what else I could have done to keep my vision in good shape.”

By L. C. Leach III