To say Sara Campbell was having a day from hell is a gross understatement. She and her husband, Matt, had spent the last eight hours driving from Summerville to his parents’ home in Washington D.C., to gather with his family upon his mother’s passing.

“We’d been there less than two hours when my phone rang. I’d just spoken to my sister Amy who said, ‘Please tell Matt and his family how sorry we are,’” Campbell remembered.

The phone call was a family member telling her that Amy, who she had just spoken to, had passed as well.

“It was surreal. I felt like I’d been sucker-punched,” Campbell said.

She explained that her sister, Amy Kline Amigoni, age 42, had been having some health issues: “She hadn’t been feeling quite right.” But there apparently had been nothing to stop her from performing her duties as a full-time chef, nothing to stop the tempo of life with two teenage daughters.

Her husband had come home and found Amy unconscious. Rushed to the ER, she was kept alive mechanically for the 13 hours it took Campbell to race to Kansas to say goodbye. On April 13, 2018, because Amy’s brain had been deprived of oxygen for too long prior to her husband’s discovery, she was pronounced brain dead.

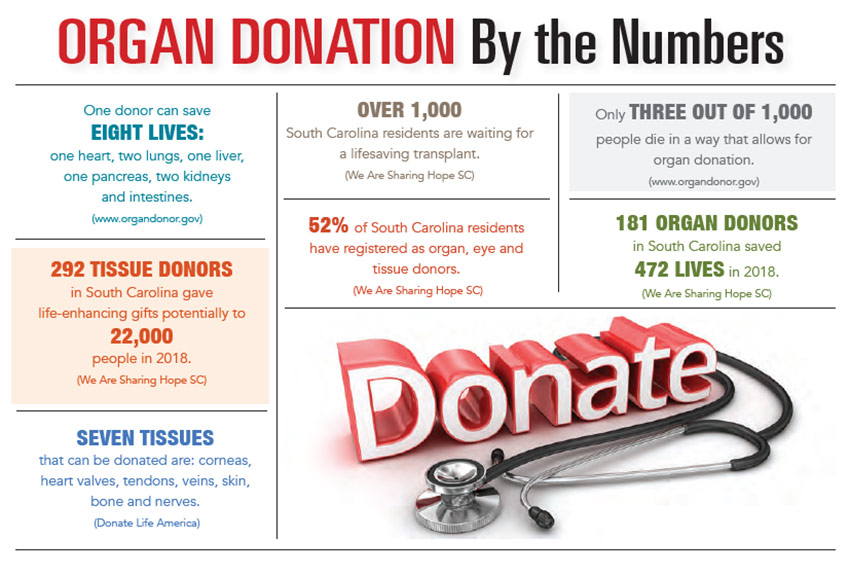

Upon her death, Amy Kline Amigoni became a full organ donor. As a result, Campbell joined a very special community, which includes South Carolina’s federally designated organ procurement organization, We Are Sharing Hope SC, which honors the legacies of heroes who say “yes.”

Campbell stated, “They did such a great job of making us all realize what a hero my sister was.”

Let’s be honest. Who doesn’t want to leave some tangible evidence of their existence on Earth? We Are Sharing Hope SC offers the opportunity to leave something infinitely more meaningful and far-reaching than a coin collection or prized apple pie recipe: your organs and tissues.

“As a full-organ donor, Amy has affected countless lives,” stated David DeStefano, executive director of We Are Sharing Hope SC.

“Her heart went to a young man,” Campbell elaborated, adding, “I recently received a letter of gratitude from a young father who now breathes with my sister’s lungs, despite the fact she was a smoker. It’s a myth that you’re not healthy enough, too young or too old to donate. Just donate. Let the medical professionals decide the outcome.”

“We are offering an end-of-life option which leaves a legacy,” DeStefano stated. “In becoming a donor hero, their impact continues in life, albeit life in a different way.”

Dr. Timothy Whelan, concurred: “Through organ donation, families see where something good can come out of tragedy.”

A transplant pulmonologist, Dr. Whelan is the associate medical director of clinical affairs for We Are Sharing Hope SC and medical director of lung transplantation at the Medical University of South Carolina.

“It’s amazing to see the excitement and joy of a transplant team upon a successful operation. There is literally a bell-ringing celebration. We see people whose lives are devastated with illness given a second chance,” he said proudly.

Registering yourself as a donor with the South Carolina Department of Motor Vehicles or online at www.DonateLifeSC.org is a great start but doesn’t mean donation is an absolute.

“There is very specific criteria a person must meet when they die for donation to be an option,” explained DeStefano, emphasizing that fewer than .5% of registered donors pass away under conditions that allow for successful organ recovery and transplantation.

Most often, donations come from an individual who has been pronounced “brain dead” in a hospital or emergency room, having suffered a complete and irreversible loss of brain function, typically from a traumatic injury, stroke or aneurysm.

DeStefano enumerated the daunting list of steps his team undertakes immediately to ensure the donated organs are received by the best candidate on the list, beginning with a search of the national database, United Network for Organ Sharing, in compliance with stringent federal regulations.

“We work 24/7/365; there are a lot of moving parts,” he said.

Frequently, the recipient is local, in part due to the viability of a recovered organ.

“A recovered heart or lungs can only survive four to six hours outside the body,” DeStefano explained, as opposed to a kidney, which is viable for a longer period of time after recovery.

A living donation – when your child needs a kidney, for example, and you are a match – is less common than a deceased donation. A non-directed living donation is extremely rare, but it does happen.

“It took me about two years to decide to donate one of my kidneys,” stated Molly Conneen, 45, after hearing a couple of podcasts about the “ripple effect” that a single, altruistic, non-directed donor could have on the lives of others. Conneen listed the five lives she directly affected by donating her kidney to a stranger. Other donors have made the same sacrifice.

“I would not be here,” stated Grace Bazzle, a poised, dynamic young woman who received her double lung transplant nearly 10 years ago.

Bazzle and her brother, Brett, were diagnosed simultaneously with cystic fibrosis at ages 4 and 5, respectively.

“Brett was put on the transplant list when he was 12. And after three ‘dry runs,’ – rushing to the hospital after receiving ‘the call,’ only to have it be a false alarm – he finally received his transplant when he was 15.”

Tragically, he never woke up from the surgery, experiencing a cerebral hemorrhage during the operation.

Bazzle was beginning her final semester at Newberry College when she realized, “I can’t do this. I’m not going to graduate.”

At 21, the bacteria in her lungs had developed a resistance to the antibiotics she’d been taking since she was 4 to combat her frequent infections.

“I was very sick, and the MUSC doctors felt it would be best to send me to Duke for evaluation. Duke began to administer a weeklong battery of tests to determine if I was a candidate for a transplant; I was so weak the doctor stopped the tests before the end of the third day and admitted me. My resting heart rate was 140,” she recalled.

Unbelievably, within four days of being placed on the transplant list, Bazzle received the call.

“My lungs came from a Roman Catholic priest in Michigan. He died suddenly of an aneurysm,” Bazzle described, in awe of the series of events that miraculously fell into place, enabling her to receive the 56-year-old man’s lungs.

Bazzle was home for Thanksgiving after surgery on Sept. 9, 2010. She’s since obtained her bachelor of science degree in biochemistry from Charleston Southern University and a master’s in biomedical science from MUSC.

“Organ donation saves lives. It gives the recipients the ability to live fully productive lives that would not have been possible otherwise,” Bazzle stated emphatically. “I would have missed out on so many wonderful life events if it weren’t for my donor’s selfless decision.”

“The impact on someone else’s life is immeasurable,” agreed DeStefano.

Grace Bazzle is living proof of that. She encourages people to educate themselves on the facts and myths surrounding organ, eye and tissue donation.

“I think people would be surprised to learn how many lives they could change through all forms of donation,” she said.

Speaking for Amy Kline Amigoni’s two teenage daughters and herself, Sara Campbell reflected, “If Amy hadn’t been an organ donor, we would all be in a much different situation. It’s a comfort to know that others are benefiting from Amy’s death. It’s an avenue of healing. Why wouldn’t you donate?”

By Mimi Wood