College of Charleston student Hannah Cramer had no intention of signing up for anything on that sunny day last spring – much less to donate bone marrow. She was merely accompanying her friend who was registering as a potential donor for Be the Match, no more than a brief detour on their way to get coffee. But her friend guilted her into filling out the short health history form. After completing the simple questionnaire and having her cheek swabbed, Cramer went about her day, feeling a tad self-righteous for having done a good deed.

Three months later, that self-righteousness long dissipated, a more powerful emotion arose – fear. Cramer received a phone call telling her that she “was a match. Wait…what?” she cringed.

But by late July 2017, when all was said and done, “it was nothing,” Cramer stated humbly. Pausing, she continued, “Well, it was something. I mean, I think I saved someone’s life. But I believe most people would do the same thing if they were asked. It was no big deal.”

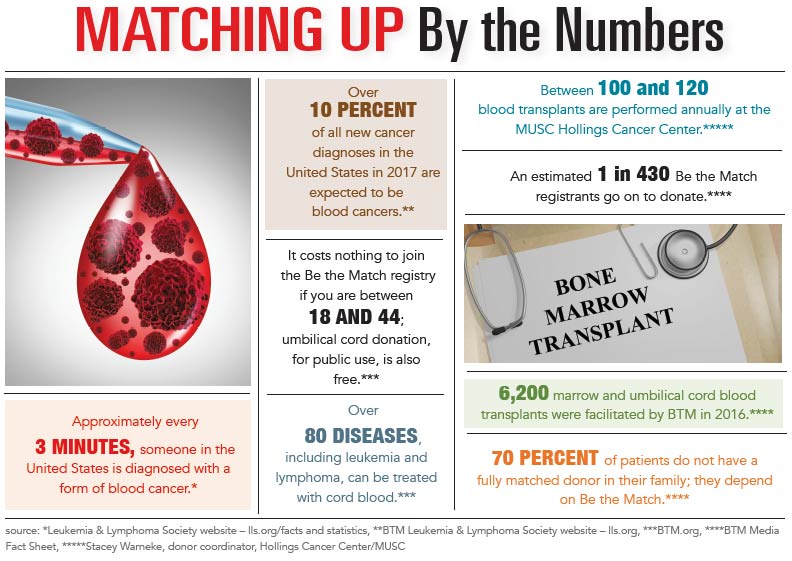

Be the Match is a nonprofit organization that maintains the largest and most diverse bone marrow registry in the world. Also referred to as the National Marrow Donor Program, “BTM is the global leader in bone marrow and umbilical cord blood transplantation,” according to Mary Halet, the organization’s director of community engagement.

Recovering her composure, Cramer listened as a donor liaison from Be the Match informed her that she was a possible donor candidate for a “female in her 40s who was sick with acute myelogenous leukemia,” a potentially fatal type of blood cancer that progresses quickly. To this day, Cramer knows little more than that about her recipient. They never met; they never communicated with each other.

“The patient’s anonymity is really protected,” Cramer explained.

Stacey Warneke, donor coordinator at the Hollings Cancer Center at the Medical University of South Carolina, elaborated: “The anonymity protects the donor, as well as the patient. We don’t want the donor to feel responsible or ‘guilty’ if the transplant isn’t successful.”

Having recently lost her father when he was in his early 50s, Cramer remembered receiving the call and thinking, “Had my dad been in a similar situation, he might still be alive. I decided then and there that I would do anything I could to help this woman.”

Cramer was an ideal candidate. The optimal donor is between 18 and 44, and, generally speaking, the younger the better. The most successful outcomes occur when the donor and patient tissue types are closely matched, usually between people sharing the same ethnic background.

“More young people of diverse racial and ethnic heritage are needed,” Halet implored.

“The most important thing a donor can do is stay committed,” she continued. “While we respect the right of the donor to change their mind and not donate, we ask everyone to think seriously about their commitment prior to joining the registry. A late decision not to donate can be life-threatening to a patient.”

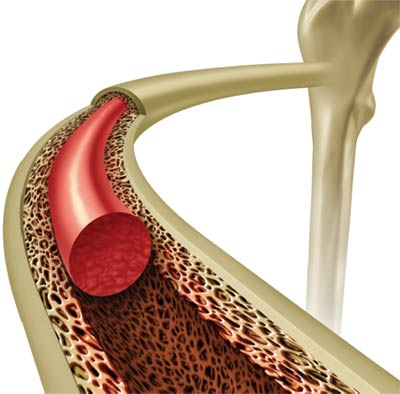

For five consecutive days prior to the procedure, Cramer went to MUSC at the same time every day to receive injections of filgrastim, a man-made protein that stimulates the production of white blood cells. The excess white cells collect primarily in the lower pelvic region, and, in Cramer’s case, caused lower back pain.

“That was the worst of it, really,” she said, describing the pain as “similar to menstrual cramps. It wasn’t bad.”

Side effects from the filgrastim injections can include headaches, nausea and bone pain.

“Most donors experience mild symptoms and generally speaking don’t complain, bearing in mind the gravity of the situation their recipient is facing,” Warneke pointed out.

There are two ways to donate. Similar to Cramer’s, over 75 percent of the procedures are Peripheral Blood Stem Cell (PBSC) donations performed non-surgically, through an IV.

“I had an IV in one arm extracting my blood, which went through a device like a centrifuge. My white cells were extracted, and my blood was returned to me through an IV in my other arm. The procedure was absolutely painless, other than the boredom of sitting still, with both arms extended, for about five hours,” said Cramer, who actively participated in a day-long sorority recruitment event the very next day.

The alternative to a PBSC donation is done surgically through an outpatient procedure when the patient’s physician requests marrow. Donating your baby’s umbilical cord, usually discarded as medical waste, is a third, exceptionally painless way to give to this lifesaving organization.

“My only sacrifice was my 21st birthday, which fell right in the middle of the entire procedure,” Cramer joked. “I wasn’t able to ‘celebrate’ the way most of my friends celebrated their 21st birthdays.”

She added that it was “totally worth it.”